Looking for ‘a better way:’ What’s wrong with SEEK and how can KY fix it?

Published 3:36 am Saturday, March 2, 2024

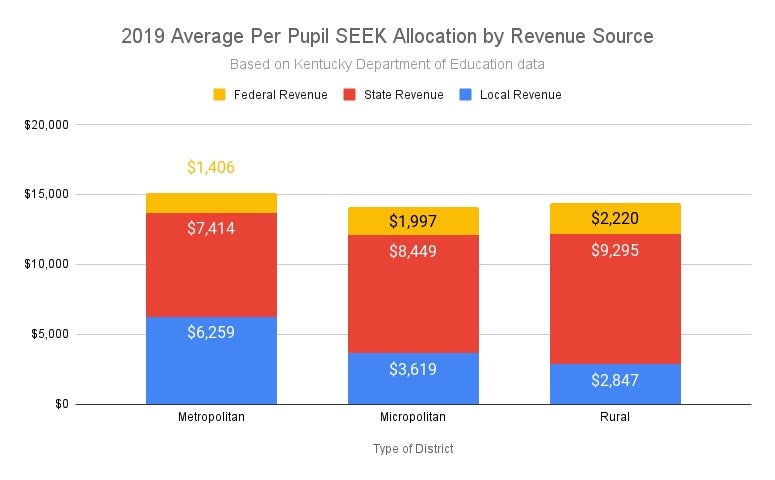

- According to Kentucky Department of Education data, the state allocates more education funds to rural districts than micropolitan or metropolitan districts, partially compensating for rural districts' lower local contribution.

According to Bowling Green Republican Rep. Kevin Jackson, a task force re-evaluating the state’s education funding formula “could be the most important thing to come out of this session.”

Last month, McKee Republican Rep. Timmy Truett’s resolution establishing the Support Education Excellence in Kentucky Task Force earned committee approval.

If the resolution passes both chambers, the SEEK Task Force will evaluate whether the formula needs to change over the interim, and if so, in what ways.

Thirty-five years ago, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled in Rose v. Council for Better Education that the Commonwealth was failing its duty to adequately fund public education.

It deemed the gap in funding between poor and rich districts—$3,489 per pupil—”unconstitutional.” Chief Justice Robert Stephens wrote that the state’s legal obligation to fund education couldn’t “be shifted to local counties and local school districts.”

In response, the legislature passed the Kentucky Education Reform Act of 1990, which raised taxes and created the Support Education Excellence in Kentucky formula.

The SEEK formula has since determined how much funding each school district gets, with minimal alterations since 1990.

SEEK’s original goal was to close the equity gap. However, a 2023 report by the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy found that the equity gap between poor and rich districts had actually widened since 1990, when KERA took effect. The gap now stands at $3,902 per pupil.

How does SEEK work?

The SEEK formula is complex. It centers around a base amount of funding per pupil, set by the General Assembly during budget years.

Right now, base funding sits at $4,200, and the proposed House budget would raise it to $4,455 by mid-2025.

The formula includes several “add-ons” for specific populations, like English learners, special education students and economically disadvantaged students.

It requires local districts to levy taxes of at least 30 cents per $100 of their assessed property value, with the option to raise more.

Most of the SEEK inputs, including a portion of local tax revenue, goes into a statewide pot of SEEK money, which is then “equalized,” or redistributed equitably across the Commonwealth’s 171 school districts.

This means that poorer districts get higher portions of state funding in an attempt to make up for lower property assessments and smaller tax bases.

In growth districts like Warren County Public Schools and Bowling Green Independent School District, that means some tax revenue raised locally doesn’t stay in the district, and is instead diverted to poorer districts.

The resolution’s sponsor, McKee Republican Rep. Timmy Truett, said that until recently, many lawmakers were under the assumption that the state simply wrote a check to districts for whatever base funding amount they decided on in the budget.

“When they say we’re going to increase SEEK funding 4% this year and 2% the next year, that doesn’t mean that Bowling Green and Warren County are going to get a 4% raise in SEEK funding because they’re a growth district,” Jackson said.

What’s changed?

While the SEEK formula has gone mostly unchanged in the past three decades, the Commonwealth has not remained as stagnant.

As population shifts from rural areas to urban and suburban areas, average daily attendance and property assessments have been “relatively volatile,” said Chay Ritter, director of the division of district support in the Kentucky Department of Education’s finance office.

While Kentucky’s predecessors built a “good foundation,” they didn’t anticipate assessments getting this high, Ritter added.

After the pandemic, attendance is suffering, leading to fluctuating funding, said Interim Education Commissioner Robin Kinney. And rising inflation has also impacted school districts, whose state allocations don’t stretch as far as they used to.

Not to mention, the demographics of Kentucky’s schools have changed, with more English learners in classrooms.

All these environmental changes warrant another look at SEEK, Kinney said.

Base funding

The SEEK formula base funding per student is based on average daily attendance.

Seven states use ADA to determine base funding, while 21 states use student body membership counts.

Kentucky’s base funding is the lowest among surrounding states. Some, like West Virginia and Illinois, opt for a resource-based funding formula instead.

The budget’s proposed SEEK increase doesn’t allow districts to provide adequate teacher raises, said Bowling Green Independent School District Superintendent Gary Fields.

If BGISD used 100% of its SEEK allocation on raises, the district could offer its teachers a 2.5% raise next school year and an additional 1.5% raise the year after.

“That’s not keeping up with inflation,” Fields said. “We’re not even just standing still, we’re going backwards again.”

Fields said the ideal base amount would be $4,500 in the 2024-25 school year and $4,900 the following year. That would allow for a 10% raise over two years that outpaces inflation and improves recruitment and retention efforts.

As it stands, the legislature is “tremendously missing the mark,” Fields said.

A 2021 Office of Education Accountability report analyzing Kentucky education funding tested dozens of hypothetical changes to the SEEK formula.

It measured the effect on equity, noting how much each formula change increased funding for the poorest districts—compromising the bottom 20%—relative to the funding for the wealthiest districts in the top 20%.

The report found that replacing average daily attendance with membership would increase equity in the poorest districts by $364 per pupil, and would also increase equity in the median districts.

Increasing the base per pupil amount to adjust for inflation increased equity in the poorest districts by $156 per pupil.

Add-ons

The SEEK formula includes carve outs for students who require additional funding support.

Louisville Democrat Rep. Tina Bojanowski thinks they need to be adapted. She said she wants research to determine the actual costs of educating these groups.

Exceptional and at-risk learners

One carve out is for students with disabilities. There are three tiers of extra funding, weighted differently based on disability severity.

The 2021 OEA report found that calculating the exceptional learner add-on using a different tiered system involving the percentage of students in a district with a disability would increase equity in the poorest districts by $887 per pupil.

The SEEK formula also allocates extra funds to districts based on the percentage of students at or below 130% of the poverty level. This is calculated by how many students get free lunch or participate in SNAP.

The OEA report found that increasing the at risk add on from 15% additional per pupil funding to 60% increased equity in the poorest districts, but hurt equity in median districts more.

It also found that adding a foster care add-on didn’t have a significant impact on equity.

Limited English Proficiency

Many school districts are spending “exorbitant amounts of money” educating English learners, Kinney said.

One such district is Warren County Public Schools, home to students of 90 nationalities who speak over 120 different languages.

WCPS spends about $5.6 million of its general fund to educate EL students. The state contributes about $600,000 of that, meaning that WCPS picks up the bill for an additional $1,684 per student.

Across the county, nearly a quarter of Bowling Green Independent’s student body are English learners. Fields has asked legislators to double the SEEK allotment to $812, but admitted even that wouldn’t come close to covering the actual cost.

It’s about more than being welcoming, Fields said. Educating English learners is a crucial step in filling all the new jobs coming to Kentucky.

“It’s really an economic development question as much as anything because we cannot continue to grow if we exclude our refugee students and families,” Fields said.

Potential rural district add-on?

Kentucky’s rural districts have a higher percentage of students who are living in poverty, have disabilities and don’t meet ACT reading and math benchmark scores, according to the OEA report.

While the state and federal governments allocate more to rural districts than metropolitan districts, their significantly lower local contributions leads to rural districts getting $717 less in total per pupil funds.

Commissioner Kinney said that creating a new add-on category for rural or sparsely populated districts should be considered. Missouri, Tennessee and West Virginia already make adjustments for rural districts.

The OEA report found that add-ons for rural and micropolitan districts would increase equity in the poorest districts by $667 per pupil.

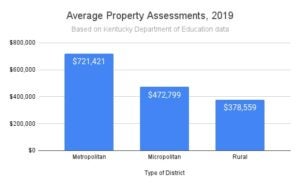

According to Kentucky Department of Education data, average property assessments in Kentucky’s metropolitan districts dwarfed micropolitan and rural assessments. Districts’ local contributions to the SEEK formula are largely based on these property assessments.

According to Kentucky Department of Education data, the state allocates more education funds to rural districts than micropolitan or metropolitan districts, partially compensating for rural districts’ lower local contribution.

Local contribution

The SEEK formula allows districts to levy additional taxes beyond the minimum property tax.

They can raise up to 15% more without voter approval, to be equalized alongside the rest of the local contribution.

Districts can go all the way to 30% if voters let them, and a portion of that will not be equalized. If the district increases the tax by more than 4% in any given year, voters have to weigh in.

The equalization component makes raising taxes a hard sell locally, Jackson said. A former school board member, Jackson said that people can stomach taxes if they know where they’re going, but knowing that it might be diverted to poorer districts elsewhere is a “hard pill to swallow sometimes.”

“It seems like we’re punishing those districts that are doing things right, that are continuing to grow and being aggressive economically,” he said.

Jackson isn’t against equity; he just wants to find “a better way, if possible.”

Ritter said there’s two sides of the spectrum: “one saying we’re doing way too much locally not getting enough from the state, and the other end is saying, ‘Well, we can’t generate as much locally because of our tax base, so we need more from the state.’ ”

Overall state funding

In 1990, state funds made up about two-thirds of education funding, while local funds contributed a third. Since then, the state share has steadily decreased as the local share has risen.

Now, the state funds about 40%, while localities pick up the remaining 60%, “due to inadequate state appropriations for K-12 education and tax breaks that reduced state revenues,” according to KyPolicy.

KyPolicy’s report argued that the equity gap is widening because wealthy districts can partially fill the hole left by a lack of state funding through additional taxes and larger tax bases. Poorer districts do not have the same tools.

“It goes back to who’s responsible for funding education,” said Louisville Democrat Rep. Tina Bojanowski.

It’s the state’s constitutional duty to fund public schools, she said, and none of the hypothetical changes to increase equity will fully work without an overall increase in state funding.

A small, inadequate pool of money, no matter how equitably it’s distributed, will remain inadequate.

“Unless you increase the net funding, there will always be winners and losers with SEEK,” Bojanowski said.

The SEEK Task Force will meet monthly during the interim. Legislators will consult stakeholders, possibly including superintendents, business owners and the Department of Education.

“It’s gonna be a long drawn out process,” Jackson said. “But it’s time for that.”